On Martin Luther King Day, a reminder of how far we have come (and gone backward)

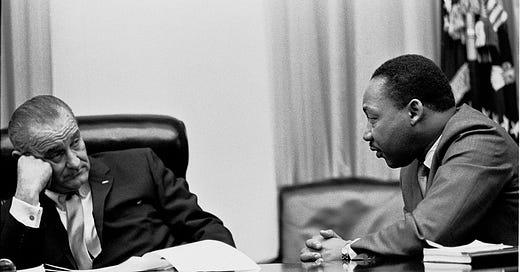

This week, we celebrate the vision and life of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

A pivotal figure — and one of the most influential Americans who has ever lived — Dr. King is now almost universally respected.

Yet King was far more divisive as a living, breathing activist. As such, it’s fitting that the living legacy of King has opened up a sharp ideological division.

All sides want to claim King’s legacy; but they disagree so strongly as to make this outcome impossible.

The side we choose in this dialogue seems to say a lot about our politics. Still, I believe that only a few people speaking today come close to the mark that King himself pursued.

And there is no better time to explain why I think so.

Perhaps the most famous quote from Dr. King reads as follows:

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

No quote I heard growing up seemed as uncontroversial as this one; and yet few quotes spoken today seem as controversial now.

Perhaps this fact alone is worthy of reflection, as a sign that something fundamental in our politics has led us toward retrogression and division.

But the points I want to make here will become much clearer after introducing another statement from Dr. King.

As shared by Jamelle Bouie (The New York Times), the second quote reads,

[S]poken and unspoken, acknowledged and denied, subtle and sometimes not so subtle — the disease of racism permeates and poisons a whole body politic.

And I can see nothing more urgent than for America to work passionately and unrelentingly — to get rid of the disease of racism. Something positive must be done. Everyone must share in the guilt as individuals and as institutions.

The government must certainly share the guilt, individuals must share the guilt, even the church must share the guilt … The hour has come for everybody, for all institutions of the public sector and the private sector to work to get rid of racism.

…

It’s all right to tell a man to lift himself by his own bootstraps. But it is a cruel jest to say to a bootless man that he ought to lift himself by his own bootstraps. We must come to see that the roots of racism are very deep in our country, and that there must be something positive and massive in order to get rid of all the effects of racism and the tragedies of racial injustice.

One often gets the sense that quotes like this one are shared as a sort of counterpoint, or rebuttal, to “I Have A Dream.”

There’s been a debate raging recently about Critical Race Theory, and quotes from Dr. King are often used to inject him into the discussion.

“I Have A Dream” is supposed to mean that King would denounce or ban CRT, because he wants a postracial future. And the other quotes are supposed to suggest that King, to the contrary, would have embraced CRT, Ibram X. Kendi, contemporary “woke” politics, and so on.

The entire debate seems pointless, really: like trying to guess whether Jesus would be inclined to vote Green rather than Democrat during His second coming.

Nevertheless, the quote Bouie shared is interesting because it reveals an attitude fundamentally opposite to 2020s CRT. Since King’s time, I argue, the entire political discourse has shrunk back from King’s vision of what is possible.

One of the great architects of CRT is named Derrick Bell.

Writing in the 1990s, Bell articulated a position that can be summed up with a name that developed later: Afro-Pessimism.

That is, in contrast to King’s wishes — to “work passionately and unrelentingly … to get rid of the disease of racism,” “to get rid of all the effects of racism and the tragedies of racial injustice” — Bell promotes a thing he calls “racial realism,” which rejects those aspirations explicitly.

“The core message of Racial Realism is that the racial domination and subjugation of blacks in America is immutable,” writes john a. powell. That’s because, Bell contends,

Black people will never gain full equality in this country. Even those herculean efforts we hail as successful will produce no more than temporary “peaks of progress,” short-lived victories that slide into irrelevance as racial patterns adapt in ways that maintain white dominance. This is a hard-to-accept fact that all history verifies. We must acknowledge it and move on to adopt policies based on what I call: “Racial Realism.” This mind-set or philosophy requires us to acknowledge the permanence of our subordinate status.

A message this bleak obviously failed to catch on at the end of the 20th century. It was only later that the thought truly flowered, first with Frank Wilderson’s Afro-Pessimism (the name of a school of thought and later a book), and afterward with the ultra-influential work of Ta-Nehisi Coates and Ibram X. Kendi.

Coates, especially with his autobiography Between the World and Me, attained a form of cultural and intellectual hegemony that is almost unparalleled in the world of racial theory.

Just look at the reception Coates received in The Washington Post:

In early 2014, … Ta-Nehisi Coates got caught up in a skirmish over who should be deemed America’s “foremost public intellectual.” …

The episode is worth recalling now only because, in the year and a half since, Coates has won that title for himself, and it isn’t close. … “Among public intellectuals in the U.S.,” writes media critic Jay Rosen, “he’s the man now.”

We should note the kind of thinking that lifted Coates to such stardom was much closer to Bell’s than to King’s — eradicating racism is utterly off the table in Coates’s writing. As Melvin Rogers explains, Coates “embraces the certainty of white supremacy and its inescapable constraints.”

Coates writes,

[My mother] knew that the galaxy itself could kill me … And no one would be brought to account for this destruction, because my death would not be the fault of any human but the fault of some unfortunate but immutable fact of ‘race,’ imposed upon an innocent country by the inscrutable judgment of invisible gods. The earthquake cannot be subpoenaed. The typhoon will not bend under indictment.

Such a morose perspective characterizes much of the popular thought in racial theory post-Bell.

The focus of the thought is all on understanding or reconceptualizing white supremacy as a thing of galactic proportions — as a literal force of gravity, in Coates’s words — and not on promoting any method for actually achieving a world without racial discrimination.

Indeed, we’ve reached a point on race where a world without discrimination cannot even be imagined.

Consider the work of Ibram X. Kendi, for example, and late-CRT scholarship from discipline founders such as Kimberlé Crenshaw.

For Kendi, the most important thing is saying racism inhabits every single law and institution that does not actively racially discriminate as a form of compensation for racial imbalances.

“There's no such thing as a ‘not racist’ or ‘race neutral’ policy,” Kendi has insisted, just as there are no “not racist” people.

Crenshaw seems to agree. Arguing that we should “See Race Again,” she and other authors contend that “the ideal of colorblindness as the default position for social justice actually functions as a color-conscious tool crafted to protect white preferences and privileges.”

In sum, the object we should be after is to get rid of the colorblind, the neutral, the “not racist.” But then what?

Even if equal material outcomes were ensured by a permanent and all-powerful antiracist bureaucracy — as Kendi proposes — the fate of materially well-off Asian-Americans in the U.S. shows that race discrimination would hardly disappear.

Kendi’s solution is basically to confess that there is no solution:

The only remedy to racist discrimination is antiracist discrimination. The only remedy to past discrimination is present discrimination. The only remedy to present discrimination is future discrimination.

A truly depressing thought.

What unites most contemporary racial theory is to deem impossible, either explicitly or implicitly, any society in which it is actually conceivable to judge people by the content of their character.

Kendi’s “Department of Antiracism” would make such a judgment formal, but an interminable project to Counter Colorblindness, as promoted by Crenshaw, basically amounts to the same thing.

All of these works — Bell, Crenshaw, Kendi, Coates — skyrocketed in popularity among a tight-knit group of people for a clear reason: their seeming racial realism.

But we should remember that “unrealistic” visions of racial progress once shook and remade the entire United States. The aftershock of the ’60s could be felt as late as 2011, when an astonishing 54 percent of black Americans reported they believed King’s dream of racial equality had been realized.

I think it’s tragic but true that we’ve been set back, at a psychic level, since that time. We are affected culturally and even spiritually by the death of racial optimism.

It is a wound that hardly anyone mentions: to pretend that racism has ceased altogether is not optimism either.

And so we tend to mark King’s holiday not with a serious reflection on what his optimism meant, but with even more calls for “realism.” We have inverted the message from King entirely.

It is our presumptuous thinking, that we know what is realistic, which leads to our scathing commentary on out-of-touch liberals or Dixiecrat conservatives.

Perhaps what we really need is less realism — and more of King’s optimism — after all.

Your free subscription inspires this work! Deliver news and analysis right to your inbox: