The Strange, Racist Politics of COVID-19

Flip open The New York Times, The Washington Post, and any of a number of mainstream national outlets, and you’ll get the impression that a concept known as vaccine hesitancy comes in a number of different flavors. Resistance to the Covid-19 vaccines is sort of like an ideological ice cream — only there’s a strange, racial charge to the flavor each group will be claimed to pick.

A telling example came in the Times’s newsletter, back when the paper was first beginning to describe the SARS-CoV variant known as Omicron. I didn’t realize at the time, but the link that the Times carefully drew — between vaccine hesitancy and low vaccination rates throughout the continent of Africa — relied much more on a kind of racist reductionism than on any sort of scientific rigor.

The newsletter used an anecdote about South Africans turning down vaccine shipments from Johnson & Johnson and Pfizer to argue that vaccine hesitancy was a main driver of Africa’s low vaccination rates.

Had I taken the Times at its word, I would have seen the continent, by far the least vaccinated in the world, as a land of noble but foolish victims; as a population that unfortunately — but understandably — fears to make use of plentiful prophylactic drugs flowing in from the West.

But the actual numbers used in this narrative contradict it. Quite dramatically, in fact. The story reveals itself to be a racial caricature, but it’s one that clearly isn’t even intended to describe a reality. The real purpose seems to be far more interesting and political.

Africa

One study cited by the Times for South Africa shows the country has a racial divide when it comes to vaccine acceptance and hesitancy. But this fact appears to have no bearing on actual vaccination rates. Witness this report from the Human Sciences Research Council:

Key findings include:

• That vaccine acceptance increased between round 3 of the survey and round 4, from 67% to 72%.

…

• Vaccine acceptance declined amongst White adults from 56% to 52%, while it increased from 69% to 75% for Black African adults. However, White adults were more likely than Black Africans to have been vaccinated (16% compared to 10%).

These stats so weaken the narrative in the Times, they deserve to be further broken down.

South Africa is a country whose vaccine hesitancy can be computed at 28 percent, but the country was only 35 percent fully vaccinated when the Times articles debuted. Racial links between vaccine hesitancy and actual rate of vaccination were lacking as well: with 23 percent greater vaccine acceptance, South Africa’s black population nonetheless had a six percent lower vaccination rate. This finding suggests strongly that factors outside of vaccine hesitancy have slowed vaccination for South African populations.

The same trend holds true in other parts of sub-Saharan Africa. Kenya, for instance, has about 10 percent lower vaccine acceptance than South Africa (63.5 percent vs. 72 percent, on similar dates). But Kenya has only reached a 6.5 percent vaccination rate in recent figures, leaving a 57-point gap between its rate of vaccine acceptance and the percentage of people actually vaccinated. Such a profound difference makes it ludicrous to blame personal hesitancy for Kenya’s slow rate of vaccination. Nonetheless, The New York Times insinuates that vaccine hesitancy is the “common thread” that links various African countries, resulting in a vaccination rate of under ten percent across the continent.

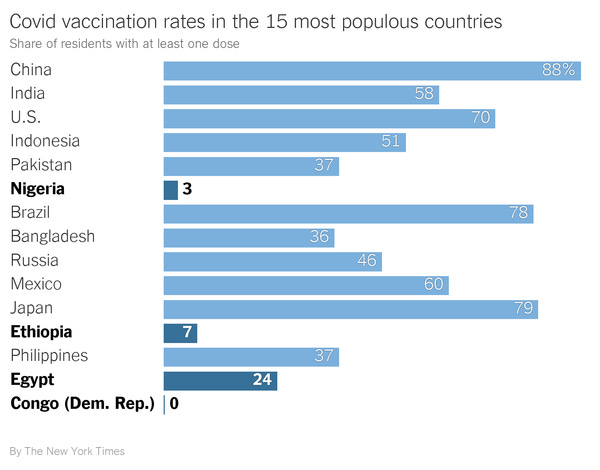

After beginning this piece, I found an article in STAT that concurs strongly with my position and rejects that of the Times. So egregious were the errors in the latter, “The New York Times and other outlets” are called out in STAT by name as the sources of a distorted reality. But there was no need even to open the STAT piece to see the absurdity at work — a chart in the Times’s newsletter indicates a three percent vaccination rate for Nigeria, a seven percent rate in Ethiopia, and a zero percent rate in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Are we really supposed to believe that zero people in the DRC want Covid-19 vaccination? Only three percent of folks in the world’s seventh-most populous country, Nigeria, are seeking inoculation?

Obviously not. The STAT article clarifies that in countries such as Uganda, word of vaccine availability brings crowds of “hundreds of people” to Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital. Folks will “wait for hours in the sweltering heat outside the hospital’s always full vaccination tent,” and “many are turned away when vaccine doses run out.” Teams responsible for a million people’s inoculation sometimes receive shipments “as small as 200 doses;” and the overall vaccine stock can serve just 15 percent of Uganda’s population.

It turns out that polling in Africa shows rates of vaccine acceptance that rival the United States. STAT cites polls convincingly in this regard. Declined vaccine shipments, in turn, most likely result from “poorly coordinated donations and the difficulty of moving doses to rural areas.” Other vaccine challenges in Africa include “receipt of expiring doses, receipt of large numbers of different types of vaccines with unique storage and transport requirements, over-centralized vaccine production, profiteering in the pandemic, and more.”

In all of this, there’s something curious at work. Not only have the Times and other outlets constructed a narrative without any quantitative support; the same story has also been promulgated by (U.S. president) Joe Biden, (White House press secretary) Jen Psaki, and (Pfizer CEO) Albert Bourla. All have implied a link between few vaccines in Africa, rampant local hesitancy, and even phenomena such as the emergence of the Omicron variant. But why would they do such a thing? And what helps the world believe these narratives?

America

I’ll take the two questions in reverse order.

The most obvious answer for how “African hesitancy” became a plausible narrative line is simply racism. This, of course, comes in the form of crude stereotypes rather than hatred. A kind of benevolent racism about Covid attitudes can be casually uttered without appealing to polled evidence, or even a solid anecdote in some cases. Typically, the racism comes with a covert political purpose and appeals to unconscious biases (although the latter are not always racial).

President Biden, for example, had a curious explanation for why Hispanic Americans experienced slow vaccination rates in mid-2021:

It’s awful hard, as well, to get Latinx vaccinated as well. Why? They’re worried that they’ll be vaccinated and deported.

It didn’t seem to matter that the U.S. Hispanic population, by most estimates, is almost 90 percent documented (Brookings Institute estimates about 6.85 million undocumented residents had Hispanic origin in 2017, in a population of 58.57 million Hispanic Americans). The only requirement for Biden to state his claim was the claim gelling well with some people’s preconceived notions about U.S. Latinidad. Stereotypes could override the complete absence of evidence tying vaccine hesitancy to deportation fear.

Similarly, Biden claimed that it was “harder to get African Americans, initially, to get vaccinated: because they’re used to be experimented on — the Tuskegee Airmen and others.” Setting aside the confusion between the Tuskegee Airmen (a group of black WWII pilots) and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study (an unrelated and unethical experiment on a group of black men), Biden was repeating a popular trope about black Americans and vaccines: one that always lacked quantitative proof.

Experiments have found that somewhere around half of black people even know about the Tuskegee experiment; still more studies have shown no racial disparity in willingness to undergo biomedical procedures, along with findings that “no association” exists “between either awareness or detailed knowledge of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and willingness to participate in biomedical research.” Even more investigations have found little link between the Tuskegee Study and Covid vaccination.

As such, the irrepressible notion that black people “are used to being experimented on” always stood as a crude and racially fraught way of looking things. And yet it matches up — almost to the letter — with what the Times put forward to describe vaccine hesitancy in Africa.

A section called “A legacy of mistreatment” in the Times’s newsletter details how a “lack of [African] vaccine education” has supposedly meshed with an underlying vaccine mistrust rooted in a “history of horrific experiments under colonialism.”

This line belies the data compiled by STAT — large African surveys in which “79% of respondents said they would get vaccinated against Covid-19” and other studies showing 67 to 89 percent vaccine acceptance across Africa — but such lines almost always do.

The reason these narratives sound plausible is racism: it’s easy, for many, to see relatively impoverished and exploited populations holding views that would otherwise be termed “childish” or “backwards.” The far more interesting question is motive. Why do these opinions about racial groups get voiced in the first place?

Noble Hesitancy

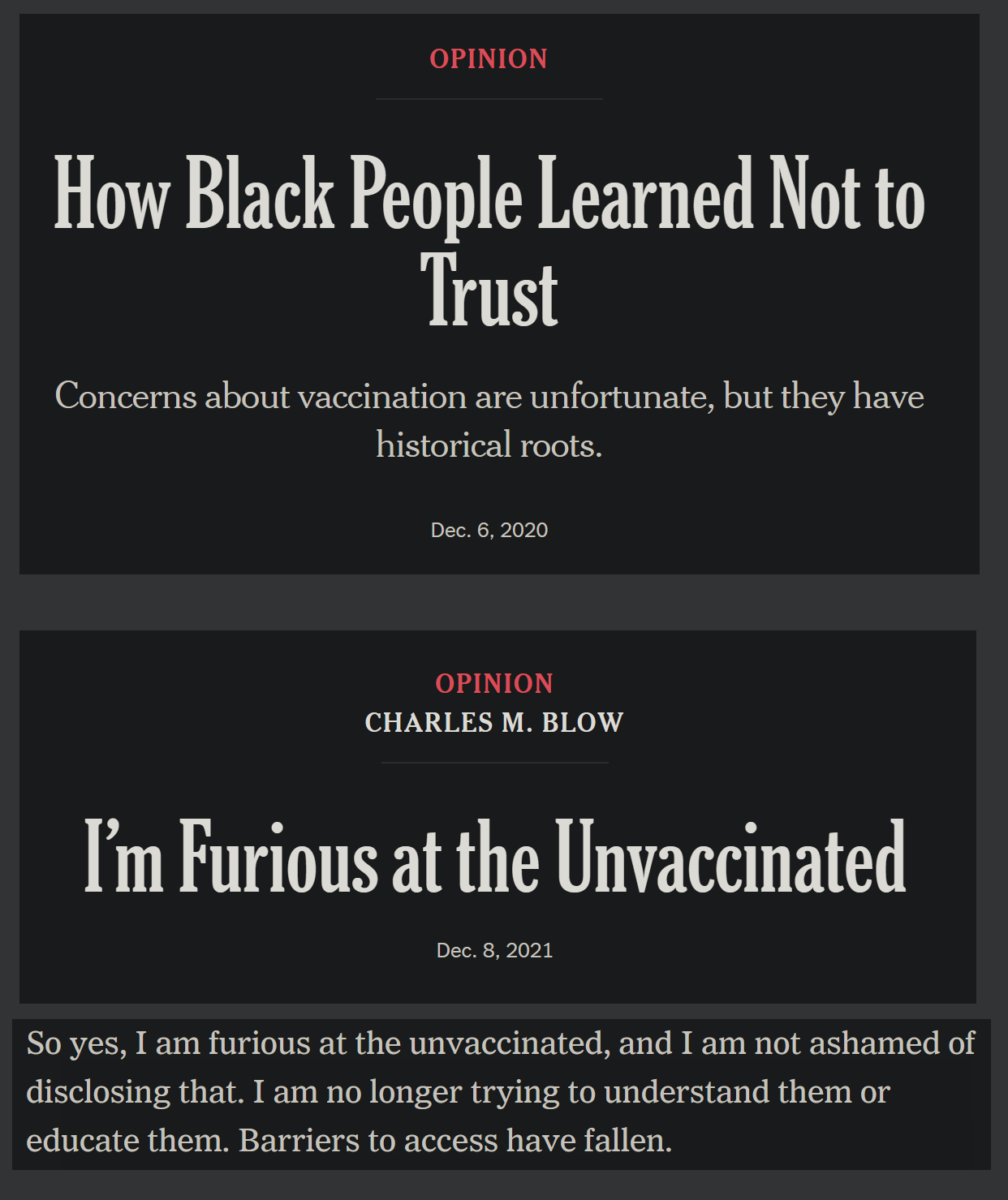

The sheer speed at which the black-people-hate-experiments line and the Hispanics-are-afraid-of-vaccine-deportation line evaporated from polite discourse should make something clear: these narratives are dreamt up and discarded ad hoc for political purposes. There has been a feeble attempt or two to say that black people have actually been dissuaded from fearing experimentation in the span between July and October — certainly one of the greatest ideological achievements no one ever seems to talk about — but even this absurd line of argument gets contradicted by other reports, in the same outlets, about slow vaccination in certain communities of color. The narratives don’t disappear when they’re disproven; they were never proven in the first place. They disappear because of the political environment. “Black Americans Changed Their Minds About Covid Shots,” according to The Times, right after Joe Biden declared that he would make vaccinations mandatory for large swathes of Americans.

The announcement of the mandates signaled a real political shift. Before, it was practically required to talk about a variety of different types of vaccine hesitancy in the U.S. Vaccinations lagged in certain groups, so there was black “Tuskegee and experiments” hesitancy, Hispanic “we’ll be deported” hesitancy, and the garden-variety hesitancy generally attributed to Republicans. The post-mandate reality was all about collapsing these various differences: there would only be the vaccinated, whom Biden portrays as good and moral people who have “made the right choice,” and the unvaccinated, who have put the country in danger and doomed themselves uniformly to “severe illness and death.”

The old forms of diverse vaccine hesitancy worked politically: the forms found in communities of color were construed as noble and justifiable. Vaccine partisans could hector the unvaccinated with unrelenting venom and still dodge accusations that their attitudes were discriminatory. Meanwhile, voters of color, to whom Democrats very much want to appeal, received a pass on their trepidations about the vaccines. This whole schema had to change once the Democrats fully embraced mandates: the thinking “evolved” so that mandates themselves, and mandate-partisan politicians, couldn’t be called discriminatory.

But that doesn’t mean the concept of noble hesitancy has lost political utility. It can still be put to work to explain the rise of new, vaccine-resistant coronavirus variants, blaming African backwardness while reinforcing the good sense of vaccine mandates. Thus, the Times asserts, without evidence,

The sources of [vaccine] skepticism are different in the U.S. and in Africa. In much of Africa, they are related to decades of exploitation and poverty. In the U.S., the biggest cause is political polarization: More than 35 percent of Republican voters are unvaccinated, compared with fewer than 10 percent of Democrats.

In other words, the vaccine skepticism in Africa — which the Times hardly substantiates — apparently has nothing to do with politics, across an entire continent of 1.3 billion people and 54 countries, but virtually all of the hesitancy in the U.S. is political.

On a factual level, it’s almost amazing this has made it into print. One of the many problems with this logic is that mainstream outlets had just been telling us for months that minority vaccine hesitancy was apolitical and noble; meanwhile, the black population remains closer to Republican vaccination levels than to Democrat ones. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation vaccine monitor, Republican vaccination stands at 59 percent of adults, black vaccination at 67 percent, Hispanic vaccination at 76 percent, and Democrat vaccination at 91 percent. (There have also been “decades of exploitation and poverty” in the United States, of course.)

STAT’s rebuttal to the Times’s new concept of noble African hesitancy is crucial. It asks the all-important question, cui bono? — who actually benefits from the invention of this new story? I think that most of the answer lies below:

At best, claims of widespread vaccine hesitancy across African nations are uninformed speculations, not supported by data. At worst, they are deliberate attempts to distract audiences from the injustice of unequal access to lifesaving Covid-19 vaccines by blaming Africans.

Indeed, one party who benefits substantially from the Times’s opinion is the collective known as Big Pharma, the people who do not want the precedent of vaccine IP being shared in an emergency. The narrative they want us to believe is there is plenty of vaccine to go around — it would definitely be helpful to vaccinate the world, but the world is just so darn resistant to vaccination! More generally, this helps exonerate the ruling class, because they might be pressured to help more with medical infrastructure etc. if influential people believed their rapaciousness keeps the poors bereft of vaccine.

But there is another element here that ties back to the Democratic Party. In remarks to the press, Director-General of the World Health Organization Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus has called for a halt to vaccination in most wealthy-country populations, along with a global moratorium on booster shots. Such ideas contraindicate broad-scale vaccine mandates and vaccine passports, which Democrats like, so the readership of The New York Times should not be allowed to think such ideas are necessary. Enter noble hesitancy, the perfect counterpunch to statements from Tedros like the following:

No more vaccines should go to countries that have already vaccinated more than 40% of their population, until COVAX has the vaccines it needs to help other countries get there too.

No more boosters should be administered, except to immunocompromised people. Most countries with high vaccine coverage continue to ignore our call for a global moratorium on boosters, at the expense of health workers and vulnerable groups in low-income countries who are still waiting for the first doses.

If The New York Times, Joe Biden, and Pfizer insinuate that hesitant Africans have kept the global poor unvaccinated, then the status quo of an unvaccinated Global South, with compulsory vaccination in the Global North, is the best conceivable outcome. Data now suggest that the best vaccines — sans boosters — are only 33 percent effective against Omicron infection, and Omicron may not have originated in Africa at all, but these facts will be buried in favor of an invented and racist, but noble, form of vaccine hesitancy. For the facts themselves, the fate that awaits is familiar: relative obscurity and mainstream news disappearance.

Your free subscription inspires this work! Deliver news and analysis right to your inbox: