Three Signs You’re Reading a Fake Story About Animal Paste

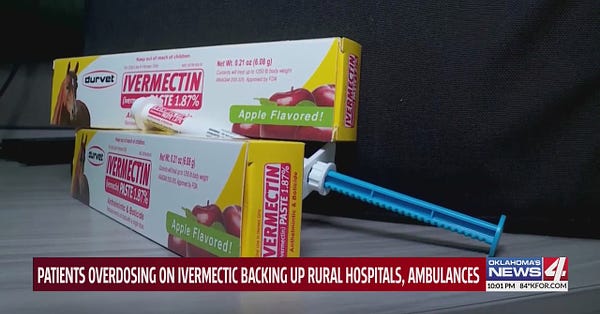

A viral story claimed that hospital beds were full of victims who overdosed on animal dewormer, but the reporting raised numerous red flags.

A story about rampant misuse of ivermectin — which broke into national headlines last week — has turned out to be a misleading fabrication. The error is just the latest in a series of mistakes, another fake scoop that the media slurped down as happily as a conspiracy junkie with animal pills.

The ivermectin story came originally from Oklahoma news outlet KFOR.

Reporter Katelyn Ogle interviewed a “rural doctor” who allegedly claimed that numerous “patients . . . taking the horse de-wormer medication, ivermectin, to fight COVID-19” had caused “emergency room and ambulance back ups” in Oklahoma hospital systems.

The story spread like wildfire. It spun off into articles from Rolling Stone, Newsweek, Business Insider, and The Guardian; it germinated further in a live news story from MSNBC’s Joy-Ann Reid and countless tweets, including a yet-to-be-retracted missive from Rachel Maddow.

Fortunately for Oklahoma, the premise of the story was completely unsubstantiated and fundamentally inaccurate. This led to a series of contradictory reports and retractions.

One hospital reported that the doctor behind the scoop, Jason McElyea, went on record to claim his quoted comments “were misconstrued and taken out of context.” Another hospital confirmed that it had taken in no cases whatsoever related to either ivermectin overdose or complications. And most alarmingly, these facts and others led to a damning “update” published in Rolling Stone, tantamount to a full retraction of the story it originally reported. The updated article reads,

One hospital has denied Dr. Jason McElyea’s claim that ivermectin overdoses are causing emergency room backlogs and delays in medical care in rural Oklahoma, and Rolling Stone has been unable to independently verify any such cases as of the time of this update.

The National Poison Data System states there were 459 reported cases of ivermectin overdose in the United States in August. Oklahoma-specific ivermectin overdose figures are not available, but the count is unlikely to be a significant factor in hospital bed availability in a state that, per the CDC, currently has a 7-day average of 1,528 Covid-19 hospitalizations. [Emphasis mine.]

Such outright sloppiness in reporting should be a cause for self-criticism, if not downright embarrassment, for a media establishment that so broadly and efficiently disseminated these factual distortions. But we can rest assured that no serious reckoning for the media is forthcoming.

Not only does the original Rolling Stone article — based on the now-discredited KFOR reporting — still exist in full below the outlet’s voluminous update/retraction; the original text still includes a line referring to Joe Rogan as a “podcaster and anti-vaccine conspiracy theorist.”

This very penchant for narrativizing — the production of a historical record in real time — has been the avowed mission of much of the press since Donald Trump’s political ascension. Jim Rutenberg puts it this way in a seminal New York Times op-ed: “It is journalism’s job to be true to the readers and viewers, and true to the facts, in a way that will stand up to history’s judgment.”

Thus, no media reckoning will take place, because ironically, viewing oneself as standing up to history’s judgment explodes the need to be accurate right now. If you look misguided in the moment, history will make you look right eventually. Or at the very least, it will give you an excuse as to why you were so willing to look wrong.

This mentality helps justify shoddy coverage of everything from Russia collusion narratives to the pull-out from Afghanistan. So at a minimum, we can expect literal fake news like this month’s ivermectin story to keep coming. We should learn to detect when and where we should treat media coverage with skepticism. Luckily, the story about ivermectin in Oklahoma provided these signs in spades.

Sign 1: All Quotes Come From a Single Source

The KFOR story and its duplicates in liberal media all contained expert analysis of the situation of Oklahoma from a single individual: Jason McElyea, DO. The credentials this person brought to the table? Being a medical doctor and being based in Oklahoma.

The reporting from Katelyn Ogle suggested that Dr. McElyea had, in emergency rooms, treated patients suffering from ivermectin overdose and a variety of ensuing symptoms. But with regard to claims that an overabundance of these patients backed up emergency rooms, overwhelmed ambulance systems, and deprived gunshot victims of much-needed medical care, original editions of the ivermectin story offered no additional testimony. No hospital administrators offered their opinions — no EMT personnel, no additional doctors, no poison control reps, no patients denied emergency care, no friends and loved ones of same.

If the effects of ivermectin cases McElyea allegedly described — more on that later — were as systemic and broad-based as multiple outlets suggested in their reports, one would expect that at least a few sources on the scene would be available to offer thoughts and commentary on the unfolding situation. There were seemingly none. And intuitively, this presents a big problem.

How could a single doctor based in rural Oklahoma possibly offer a comprehensive description of events in hospital systems throughout an entire state? What’s more, all of the testimony from Dr. McElyea recounted personal experience and was therefore anecdotal — which brings us to sign number two.

Sign 2: The Story Contains No Data

Even with additional testimony, it would be difficult to confirm a story about patient triage in emergency rooms without hard numbers. Human beings are prone to all manner of biases and tend to become more sensitive about information with personal relevance to themselves. Have you suddenly noticed more Toyota Corollas on the road after your family picked one up?

Just the same, a doctor who treated a harrowing case of ivermectin overdose might start to see cases everywhere — we need to act now; the emergency room is overrun! That doctor’s opinion, in actual fact, may or may not line up with the actual proportion of hospital beds allocated to ivermectin patients vs. COVID-19 patients vs. patients with traditional injuries and maladies. Numbers help the story hang together.

Such facts made the lack of quantitative data, both in the KFOR story and in duplicates, extremely suspicious. The articles contained no case figures for ivermectin overdose, nor did they describe the number of hospital beds typically available in the affected region. In short, the stories gave no basis for informed estimates about the likely impact of ivermectin on emergency room and ambulance availability in Oklahoma.

This oversight becomes even more baffling in light of the information included in the Rolling Stone article’s corrections. Apparently, “The National Poison Data System states there were 459 reported cases of ivermectin overdose in the United States in August.”

To get a sense of the scale here, keep in mind that there were, according to Statista, 4,142,913 new U.S. cases of COVID-19 reported in the same month (Aug. 2021). Ivermectin overdoses happened at 0.011% of the frequency of COVID-19 infection.

Even if we assume that every reported overdose resulted in hospitalization, the numbers still pale in comparison to the more than 100,000 people hospitalized for COVID-19 in the U.S. this August. All 459 ivermectin overdoses would represent 0.46% of the total beds allocated to both ivermectin and COVID-19.

Ivermectin doesn’t even reflect a high proportion of the overall amount of poisonings and overdoses in the United States. A recently corrected story from Associated Press states that around two percent of calls to Poison Control in Mississippi, a deep-red state, concern the anti-parasitic drug.

Sign 3: Collected Quotes Do Not Make the Story’s Central Claim

All of this explains the final sign that KFOR’s ivermectin story was more than a little dubious. As Reason editor Robby Soave points out, Dr. McElyea’s comments to KFOR never actually connected ivermectin overdoses to hospital strain.

The doctor gave several quotes about strained hospitals, including the bombshell quotes about gunshot victims losing access to facilities and ambulances getting backed up at specific medical centers, but none of these quotes mentioned ivermectin:

“The ERs are so backed up that gunshot victims were having hard times getting to facilities where they can get definitive care and be treated.”

“All of their ambulances are stuck at the hospital waiting for a bed to open so they can take the patient in and, they don’t have any — that’s it. If there’s no ambulance to take the call, there’s no ambulance to come to the call.”

The quotes about ivermectin, in turn, did not mention hospital strain. Dr. McElyea only listed frightening side effects of ivermectin overdose and urged doctor prescription and consultation prior to taking the drug for any reason.

Taken alone, such disjointed quotes can seem innocuous, like mere quirks of editing. But without additional confirmation or numbers to back up the story, the disconnected quotes from Dr. McElyea appeared to be pieced together with wishful thinking.

The process buoying the ivermectin story, allowing it to blossom without roots in the truth, lines up well with others we’ve seen before. Journalist Matt Taibbi mused on the rudiments of this formula in one episode of his podcast Useful Idiots. Taibbi suggests that “Russiagate” — the litany of unverified claims regarding political collusion between the Kremlin and Donald Trump —

birthed a new reportorial style . . . I see elements of the same approach in lots of different stories now, where there’ll be a bit or a hint of something that will appear in the news, and there’ll be just this blizzard of editorializing that happens around it before anybody really knows what’s actually happening with the story. . . . I feel like that was a characteristic of all of these bombshells in Russiagate. Somehow they were almost pre-factual . . . the outrage happened before the information was conveyed. It’s almost become a part of the commercial formula of how we sell news.

And so it is here. The current epoch of U.S. media is hyper-polarization, as Taibbi argues elsewhere.

Pre-factual stories have, in this era, become a profitable norm. And the most partisan-sounding stories are where facts get most readily preceded. Reader beware.

To support this work, please share or subscribe to The AfterParty using the buttons below.